Falling over in the Middle of the night

Jai Alai:the world’s fastest sport

Why did the chicken cross the road?

*new posts are in bold

The hotel where my mother and I spent the summer of 1939 faced the beach, a few hundred yards away. Early in the morning, I would go to the window, hiking myself onto my elbows. I would watch, fascinated, at a slow moving line from the water’s edge to the beach huts in front of the hotel. At a crawl, a couple of dozen of women wearing bags on their backs moved along the beach with mesh strainers in their hands. They were methodically scooping every bit of detritus left in the sand the day before. By breakfast they were done and the beach would be immaculate. I’d heard a guest complain “I lost my diamond earring on the beach, I’m sure. The hotel threatened the sweepers, but no one would admit anything!” I watched the line and wondered about the supposed lost jewel. If someone found it would she jump up with a scream? Or just pocket it without a word? I amused myself imagining this while waiting for my mother to emerge for breakfast. She was habitually a late sleeper.

We were summering in Tsingtao, at a well known resort. It was about an eight hour train ride from Shanghai, but we went the longer way by boat along the coast. A special feature of the resort that included our hotel was a fronton, built to accommodate teams of Jai Alai players that came up from Shanghai. They had a permanent location there but it was too hot for summer games. The fronton was a three walled court, open for spectator seating. The front wall was made of granite to withstand the balls slugged by the players out of baskets they held in one hand. The speed of the rock hard ball, smaller than a baseball, would be close to 150 mph. It is an exciting game, very fast, as one man hurls, the other guy catches the ball in his basket and catapults it back, and so it goes back and forth, with bets being taken moment by moment and players dashing, even climbing the side walls to capture the flying ball. This establishes the background for my jai alai story, which is not going to be an account of the game itself. After spinning my head back and forth watching the action a few times, I lost interest in it and was ready to meet my chum, Jo Jo at the beach.

The speed of the rock hard ball, smaller than a baseball, would be close to 150 mph. It is an exciting game, very fast, as one man hurls, the other guy catches the ball in his basket and catapults it back, and so it goes back and forth, with bets being taken moment by moment and players dashing, even climbing the side walls to capture the flying ball. This establishes the background for my jai alai story, which is not going to be an account of the game itself. After spinning my head back and forth watching the action a few times, I lost interest in it and was ready to meet my chum, Jo Jo at the beach.

Most of the long stay summer guests at the hotel were young housewives with little children. Their husbands worked in the sweltering City. Some dads, but not many, occasionally joined their families for a weekend. My father never did. My mother, our amah, and I settled into a pleasant suite for a couple of months. Because we traveled by sea, we were able to bring trunks full of clothing and accessories. My mother was an excellent long distance swimmer, and once on the beach, would disappear into the ocean for a very long time, leaving me on the beach with my bucket and spade. My learning to swim was out of the question. “You were afraid of the water,” my mother stated with finality. About my thwarted desire to ride a bike “You were afraid to fall off.” From my Dad, about my wish to learn to play the piano “You would spend too much time inside, practicing.” At the age of five, I had already embraced reading as an activity I could pursue without opposition.

In the evenings, the young mothers would make their way to the Jai Alai stadium, and try to sit right up front. The players were Basques; handsome and dangerous looking. They were dark, compact and virile. They played their game with explosive energy. Their black eyes snapped, their oiled and curly hair dripped sweat. They were the perfect complement to the cool appearing yet seething housewives.

My mother was small, chubby and bosomy. She sat upfront with a haughty air. She shaved her legs and underarms daily and carried face powder sheets with her wherever she went. “Look at them sweat,” she said disdainfully. I was sitting by her, when Echevarria, one of the players who was squatting in front of us between sets, turned and winked at me, with a big smile. He had hair springing from his armpits, hair on his chest and furry arms and legs. “Ugh!” said my mother, “look at all that hair.”

The little balls flew from the baskets attached to each man’s arm. The crowd screamed for their favorites. My mother powdered her nose and fanned herself. At that moment, Echevarria jumped up gracefully, and turned towards us. “Madam,” he began, and smiled a brilliant, wicked smile. To my surprise, my mother who kept herself out of the sun and was very pale, turned bright red. He leaned towards her and said something, and she held out her manicured hand. He took it between his sweaty paws, and I thought my mother would snatch it away. But all I could hear was a soft murmur as they leaned towards each other and started quietly talking.

That was when my mother officially met the famous Jai Alai player, Carlos Echevarria, and I got to ride the beach daily on his muscular shoulders.

After the game, we would join him in the hotel bar, where he drank anise wine and my mother daintily squeezed a lemon quarter into her gin and tonic. She and I would then have a low calorie meal, as she was watching her weight, while he dug into a hearty paella redolent of garlic and saffron. Although his English was rudimentary, they seemed to have a conversation going. I sidled off to join my friend, Jo Jo. Her French mother was gaily laughing with HER handsome player. Our amahs came out to find us, and we were escorted back to our rooms. I was still up, reading a book, when my mother returned to her adjacent room.

There was plenty of sun and paddling in the shallows with Jo Jo, who didn’t swim either.  Echevarria offered to teach us how to swim, without success. Boys flung themselves, yelling, into the waves, but most of the little girls wore pretty outfits and built sandcastles on the beach. They were not encouraged to play sports back then. Carlos (as we now felt free to him) was not really a swimmer himself. But he would haul me on his shoulders into knee deep water, or grab my wrists and swing me around, and tell me stories about the Basque fishing village he came from. When my mother returned to shore from one of her epic swims, he would take the beach towel that amah had ready and wrap it around my mother himself. He would tip amah and shoo her away. I rarely heard my mother laugh at home, but she was different here. She giggled, and laughed out loud a lot. She would sit and watch Carlos working out at the fronton, as all the players did for hours daily. Carlos had impressive muscle definition all over his body: he could lift me up with one arm. “Don’t hurt yourself,” my mother warned him, “she’s so heavy.” Carlos laughed a lot too; as easily as he lifted me and swung me around. “No she not heavy; she light, like bird!” Of course, that summer I developed a crush on Echevarria. But more, his big hearted, generous nature; the way he saw me as my parents never did, began to instill in me a new feeling of self esteem. He had to approach my mother through me, but he really liked me as a person, I felt, and would sit by me and move his finger over the page of a book I was reading, and try to mouth the English words. “You my teacher, pretty girl” he’d say, tousling my hair affectionately. Most of the players were married with children back home. They missed their families, so they were always ready to play ball or race along the beach or build a sandcastle with the summer kids.

Echevarria offered to teach us how to swim, without success. Boys flung themselves, yelling, into the waves, but most of the little girls wore pretty outfits and built sandcastles on the beach. They were not encouraged to play sports back then. Carlos (as we now felt free to him) was not really a swimmer himself. But he would haul me on his shoulders into knee deep water, or grab my wrists and swing me around, and tell me stories about the Basque fishing village he came from. When my mother returned to shore from one of her epic swims, he would take the beach towel that amah had ready and wrap it around my mother himself. He would tip amah and shoo her away. I rarely heard my mother laugh at home, but she was different here. She giggled, and laughed out loud a lot. She would sit and watch Carlos working out at the fronton, as all the players did for hours daily. Carlos had impressive muscle definition all over his body: he could lift me up with one arm. “Don’t hurt yourself,” my mother warned him, “she’s so heavy.” Carlos laughed a lot too; as easily as he lifted me and swung me around. “No she not heavy; she light, like bird!” Of course, that summer I developed a crush on Echevarria. But more, his big hearted, generous nature; the way he saw me as my parents never did, began to instill in me a new feeling of self esteem. He had to approach my mother through me, but he really liked me as a person, I felt, and would sit by me and move his finger over the page of a book I was reading, and try to mouth the English words. “You my teacher, pretty girl” he’d say, tousling my hair affectionately. Most of the players were married with children back home. They missed their families, so they were always ready to play ball or race along the beach or build a sandcastle with the summer kids.

By the end of the summer, there had been a scandal, not surprising. One housewife lost it completely for Arriaga, one of the principal players. She sold her jewelry, and tried to bribe her amah to take her three year old daughter home. She planned to travel with her lover back to Shanghai. It was an impossible scheme, of course. The husband appeared; the hunky lover turned out not to be at all keen to elope. Basque players were and still are mostly very religious Catholics; not ready for more than a brief fling. There was plenty of gossip and taking of sides among the summer ladies, but in the end, everyone went home, discarding this season’s dresses, sandals, sun hats and lovers. “Will we see Carlos in Shanghai?” I asked my mother. “Of course not!” my mother snapped,” Why would we?” And that was the end of that story, except for an exchange of pebbles between me and Carlos on our last day.

The main fronton in Shanghai was located on the Rue des Soeurs, the same street as my school. But the entrances must have faced different directions as I never ever saw a Jai Alai player in that neighborhood. The whole, hot, charged summer faded away like a dream.

photos

The Jai Alai basket, or cistera

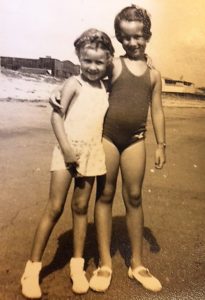

Jo Jo and Joan in 1939

Uncle Henry, as I knew him, was a familiar presence at the homes of my family’s circle, the French club, the tennis courts, the bridge tables. He was a tall man with movie star looks, often compared to Gregory Peck, and always impeccably dressed for the occasion. He was not a blood relation, but in Eurasian circles, families were extended to “went to school with” and “was engaged to” and so forth. The link was the Western ancestor, whether the person be English, Portuguese or Danish, for example, and a Chinese individual, usually a female. Some Eurasian families had a short history, like my Dad’s: Danish father, Chinese mother. On my mother’s side, the mingled history went back further. Her father was thought to be the product of an English seaman and a Chinese bar girl. “Harvey” was the name on his birth certificate, though no Dad was around. Her beautiful reddish haired mother was the daughter of a middle class Chinese midwife whose father, we recall, was an intellectual who refused to allow her feet to be bound. An English employee of the East India Company met her at her father’s shop and was keen to marry this woman, notwithstanding her full size feet. Her father gave in, as he didn’t perceive any other marital possibilities. A legal English and Chinese marriage was rare back in the 19th century; theirs was an apparent success.

I don’t know Uncle Henry’s background, except to note his presence everywhere. Uncle Henry loved children; especially little girls. He would coax me onto his lap more than once and when I was installed, managed to establish a strong grip around my abdomen. He would then somehow position my rear right against his crotch, cleverly spreading my legs to achieve a perfect fit. He would continue his conversation with the group, always smiling pleasantly while commencing a subtle (at first) gyration. In those days, men wore a suit comprising a capacious jacket and trousers, baggy by today’s standards. In the winter, a loose sweater was worn over shirt and undershirt. A four or five year old body didn’t have a chance enveloped in all this clothing. I could begin to hear a slight moan or hum coming from Henry and a definite massaging movement of something hardening between my thighs. His hands seemed to be moving around, too. It was not altogether unpleasant, but if there was a strong controlling element to this; an insistent quality, I would want to get away. No one seemed to notice anything, so I had to made a sudden move, using my elbows and sliding forward, landing on the floor, with a thump. “What’s the matter?” my mother would say to me irritably, “don’t be so clumsy!” Uncle Henry would smooth his clothing and try to help me back on his lap, but by then, I was away. I received very little affection in my life, so it felt as if Henry cared about me. I enjoyed his attention, to a point. He had a hugging technique as well. He would grab a child by the armpits and grasp her to his body with exclamations like “what a gorgeous big girl you’ve become,” etc. Of course, he always had pockets full of candy; you had to be ready to root in those trouser pocket for these goodies. I was certainly not the only lap victim. Uncle Henry would often be hugging or holding a bemused looking child; he’d even go down to the kitchen and fool around with the servants’ children. They normally never got candy, so he was very welcomed. Henry had no children of his own. He was married to Thelma, a homely, dowdy Japanese woman. She didn’t speak much English, the lingua franca of Eurasians, and she scowled and frowned a lot, but she always accompanied Henry to social occasions. Their relationship must have been what saved him from a stint in concentration camp.

My cousin, Sylvia and I were the same age, though I was much bigger. We were friends at the age of five or six, and she stayed over from time to time. We were in my big bed under the mosquito net. It was such a hot night, we had taken off our pj,s. and just lay there under the overhead fan not able to fall asleep. We started idly to explore each other’s bodies. Nipples were interesting to wiggle and pinch. Belly buttons…one inny and one outy….also interesting. We turned to face each other’s crotch and investigated with our fingers, then hesitatingly with our tongues. It felt very natural…and soon we began to feel sleepy, rolled over and fell asleep. We never thought to talk about how we had touched each other, and we didn’t have any inclination to repeat this investigation. One day the subject of Uncle Henry came up and we both chortled about him, and our techniques for avoiding close contact with him.

We were friends at the age of five or six, and she stayed over from time to time. We were in my big bed under the mosquito net. It was such a hot night, we had taken off our pj,s. and just lay there under the overhead fan not able to fall asleep. We started idly to explore each other’s bodies. Nipples were interesting to wiggle and pinch. Belly buttons…one inny and one outy….also interesting. We turned to face each other’s crotch and investigated with our fingers, then hesitatingly with our tongues. It felt very natural…and soon we began to feel sleepy, rolled over and fell asleep. We never thought to talk about how we had touched each other, and we didn’t have any inclination to repeat this investigation. One day the subject of Uncle Henry came up and we both chortled about him, and our techniques for avoiding close contact with him.

“I saw someone’s thing,” I said. “It was ugly. I was supposed to touch it but I wouldn’t.” This belonged to a Russian man who lived in a ground floor flat a few blocks away. He was often at one of his windows, which opened on the street. He’d be holding onto a chocolate bar or some toy, or even a few dollar bills, waving to children walking past as we did, unsupervised, in those days. I recall going in with a couple of other children five years old, or older. Alexey lay in bed with a table of “medical supplies” next to him and proposed we play hospital. He seemed very old and wrinkled with pale, mottled skin. Scraggly grey hair grew on his chest and groin area. He wore an open kimono, exposing the whole front of his body. He flopped up and down on his bed as he pointed to his so called wound. A nurse (one of us, of course) was supposed to apply cream to it. A boy said “I’ll do it grandpa; give me the money first.” I was transfixed as the boy picked up the flaccid muscle lying on the man’s thigh, and pumped up and down with the “Medical Cream” until it gradually became upright; a thick, veiny…well, “thing” was all I knew to call it. Alexey began to groan, at which point a couple of us grabbed a few candies and ran out of the building, laughing nervously.

“What was it like?” asked Sylvia. It was hard for me to have an opinion. I knew instinctively it was not something I could mention to my parents. I just said “It was not nice. It was ugly and scary.” My parents had separate quarters, and I recall my mother letting out a scream when my Dad unexpectedly appeared at her door while she was just wearing underwear. I never saw them in anything approaching an embrace. When the topic of sex came up, my mother once offered “women just have to grin and bear it.”

The following year I witnessed some boys in the expansive garden of the apartment building behind my house. They were gathered under some shrubs with a girl everyone knew was retarded. They had removed her panties and spreadeagled her on her back right on the ground. She whimpered a little but didn’t object as one boy poked a stick into her vagina. Again, I was transfixed as they turned her over and started prodding their fingers into her anus. She started to giggle, then. At that point I ran home. I needed to hide, and I vowed I wasn’t going anywhere near that garden again. But I had been curious, even fascinated.

Most parents, even today, have no idea of their children’s early exposure to sex. I believe all kids have been molested at some time or other by adults or other children. Unless badly damaged, we pick ourselves up and move on. Childhood itself is a concept that did not catch on till perhaps the 20th century. It still hasn’t caught on in many societies. Children were just belongings of their parents or guardians and had no rights whatsoever. They could be forced to hard labor and sex at any age. They could be beaten even to death, and sold at their parents’ will.

And that’s the summary of one tot’s sexual education.

photo: Joan and Sylvia, five or six years old

Xiao Mei entered my life in 1940 when I was six years old and Shanghai was occupied by the Japanese. World War Two meant less to me than the invasion of my life by this young girl, barely twice my age.

“So, are you planning to write about that slave of yours?” asked Phyllis. I was visiting her in the late ’80s at her home in Guelph, a Canadian town. I distinctly remember sitting down suddenly. “I forgot all about her,” I mumbled. I had buried that time deep in my memory, but at that moment, my mind flashed back to my childhood. “Well she spent at least three or four years with you,” Phyllis continued relentlessly, “how could you forget that poor girl?” Vivid images came back to me as she talked. I see myself, up a tree, demanding my breakfast. I see her expressionless face as she awkwardly climbs up the tree and hands me the tray. That image, which I suppressed for years, cuts across my vision like it just happened; the day, the sun, the tree, being alone, hating my life, hating my parents for forcing on me this ugly, dull, sad, pockmarked girl. All I can think to do is punish her for being alive. Just as I took the puppy I vehemently didn’t want and threw it down the stairs and ran into my room and screamed and screamed and screamed.

“Well, you needed a friend,” my exasperated mother said, “and Xiao Mei’s parents were glad to let us take her.” I wanted a dog, too. I had cut out photos of some big dogs to show my parents, but I was given a handbag size pup, who yapped non stop. “It’s the perfect size dog for you. You won’t have to take it for walks; you can run around the garden with it.” My mother, again, settling the issue without any chance of rebuttal. “You are not capable of managing a big dog.” Eventually I got fond of Blondie, who survived her fall, but she was never the dog I wanted. Xiao Mei was definitely not the friend I wanted.

At that age I began to shut myself in my room to have tantrums . Neither my father or my mother ever presented themselves at these events. In that big house with its solid walls and doors, I could hear my screams being absorbed and gradually sounding hoarse, pitiful and finally tiny. Xiao Mei’s job was to enter my room and try to deal with my rage. She would come in timidly, and I would stare at her through my tears. She stared back at me silently. I didn’t want her more than I didn’t want anyone or anything in my life. When I think of her now, I imagine she just made herself blank. How could she ever understand being off loaded by her family at the age of 12, and tasked to spend the rest of her childhood as my servant?

She would quietly put away the toys I had thrown around the room. She had a way of shuffling as she walked; she always moved very slowly. “How can we play badminton or ping pong; she’s hopeless!” Of course, she was illiterate. Even her spoken Chinese was not the Shanghai dialect I knew. Hong said contemptuously “the family are immigrants from the country. They have to sell their kids to survive!” His young sidekick Xiao Liu sneered “She’s ugly and dumb and her nose is always snotty.” But she was always ready to care for the chauffeur’s baby.

I can’t recall when I decided to scale back my tantrums; probably when I became friends with Raya, a girl I met in the garden behind my house where we used to play after school. Xiao Mei was gradually shifted to kitchen duties when it became obvious we were never going to bond.

My mother’s mother, Mary, had had a history of acquiring unwanted girls, training them in household duties and using their services until they reached a marriageable age. That would be sixteen or so.. My mother decided to follow suit with Xiao Mei when she reached sixteen. My mother picked out some serviceable clothing, a pair of gold earrings, an umbrella, and sturdy shoes. A husband was selected, and my mother, Xiao Mei and I set out one afternoon with a canvas dowry bag. Just a few blocks away, we turned into a side street, really a narrow alley, and my mother led us to a decrepit gate, and confidently pushed it open. “This is where we got her originally,” my mother explained. Inside was a tamped earth area, a kind of courtyard. Someone was washing clothes in a basin, and something was being pounded in a bucket by another person. A few dirty children with requisite snotty noses were crawling around, the backs of their smocks open, exposing their buttocks so they could urinate and defecate at will. Judging from the stink in the area, they did just that. A man smoking a cigarette squatted silently in front of the house in the background. It spread across the lot, a long front punctuated by doorways but no apparent doors. Xiao Mei just walked over to the house and went inside. “Well, that’s that,” said my mother, ” For all my efforts! You never appreciated anything.” I looked around at the scene; I saw poor people living their lives, seeming neither happy nor unhappy. Xiao Mei emerged with an older woman and the two of them chatted briefly with my mother, who handed over the bag and a few banknotes. “Where’s the husband?” I asked. My mother shrugged. “Hopefully working. He gets the money I brought, not that he earned it. It’s Xiao Mei’s years of pocket money.” We left shortly afterwards, no tea being offered. It felt a bit of an anticlimax, a letdown after years of barely communicating with a being given to me “As your slave!” my aunt Phyllis would repeat, “That poor, poor child!” They didn’t respect her in the kitchen, either. It was so easy for me to forget my callous behavior towards Xiao Mei; to forget her entirely, to not even remember her face or anything distinct about her. Only years later did my memory dredge her up together with a sadness, a nebulous regret. I never saw her again. I never went down that alley again, nor did she ever wander along my boulevard either.

Ed’s 5’10” body was down to 118 pounds when his camp at Pootung was liberated in August 1945. For the past three years, he had slept on a wooden plank, his belongings hung overhead.

Ed’s 5’10” body was down to 118 pounds when his camp at Pootung was liberated in August 1945. For the past three years, he had slept on a wooden plank, his belongings hung overhead.

He shoveled coal for the cooking fire, as part of the kitchen detail, scrounged for food every day, and in the process, formed great friendships with the Americans he worked with.

Ed recalled his time in camp as a great adventure. “Our kitchen team woke up every day trying to figure out how to score some food. Rodents, roaches, a dog from the Canidrome, which had been slaughtered by the Japanese, wormy rice, animal feed: these were some of our finds. We got together to collect any valuables we could trade over the fence with the Chinese vendors. By the end there wasn’t a watch, belt buckle or piece of jewelry left to any of us. I had to reluctantly let go of my dancing shoes. Why had I even thought of packing them for camp in the first place? ” Ed could not have realized at the time that his excellent ballroom dancing might later help get him into the USA. But that comes later.

Ed recalled his time in camp as a great adventure. “Our kitchen team woke up every day trying to figure out how to score some food. Rodents, roaches, a dog from the Canidrome, which had been slaughtered by the Japanese, wormy rice, animal feed: these were some of our finds. We got together to collect any valuables we could trade over the fence with the Chinese vendors. By the end there wasn’t a watch, belt buckle or piece of jewelry left to any of us. I had to reluctantly let go of my dancing shoes. Why had I even thought of packing them for camp in the first place? ” Ed could not have realized at the time that his excellent ballroom dancing might later help get him into the USA. But that comes later.

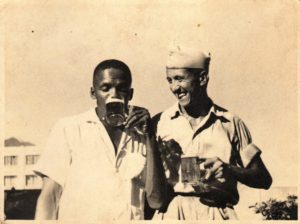

On August 19, 1945, A huge Curtis C-46 Army Transport arrived at Dazang Airfield in Shanghai on an American goodwill mission. The aim was to arrange the orderly release of Allied internees. The behemoth plane first brushed over the dingy Pootung internment camp building, with its 1700 horsepower cyclone motors roaring and an American officer waving madly from it. As soon as the inmates identified the US insignia on the plane, they went wild. They erupted from their quarters like a tidal wave. Everyone was doing something: waving flags, shouting or stomping with joy. The Japanese had disappeared. Leaflets floated down with various instructions to the inmates, “But all we needed to know is: it’s over!” Ed recalled. Soon the party began. Food, cigarettes and beer appeared over the fence. Ed celebrating here with his best friend, Dan Holden. “

We’ll meet again in California” Dan vowed. And they did, even though it didn’t work out the way they expected.

We’ll meet again in California” Dan vowed. And they did, even though it didn’t work out the way they expected.

The internees made their way home, mainly to the US. Ed found a job in Hongkong, gathered his meager belongings and moved there in 1948. This was just a waystation for him; he was determined to go to the US.

Soon after, at a dance at the Peninsula Hotel, he met Ellen, an American nurse. She recalls “he was the best dancer I had ever met. ” Ed said the same about her. They danced a whole week away every night. On his time off, he took her for picnics at the beach at Repulse Bay, where he was very impressed by her body. Ellen was a strict Catholic, so they never got beyond her boundaries. She had to return home shortly to the US, and that could have been the end of it. But she returned to Hongkong in 1949. “I couldn’t stop thinking about Ed, and how we danced and danced. People at the Peninsula used to back away and watch us. I felt like a star!”

They reunited and that same year they got married at St. Teresa’s Catholic church in Hongkong.  Ellen immediately started the procedure of getting Ed to the US. He qualified as a War Bride, and they were soon on their way to California. Years later, when one of their children asked Ellen about it, she said “it was his dancing that did it for me!” And they stayed together, raising four children. His friendship with Dan Holden did not survive the racial prejudice of the ’50s, something both always regretted.

Ellen immediately started the procedure of getting Ed to the US. He qualified as a War Bride, and they were soon on their way to California. Years later, when one of their children asked Ellen about it, she said “it was his dancing that did it for me!” And they stayed together, raising four children. His friendship with Dan Holden did not survive the racial prejudice of the ’50s, something both always regretted.

For a young, unattached man, the rigors of a concentration camp were balanced out by the strong male bonding that brought the disparate men together. “We were at our best,” Ed told me later, though he rarely spoke of those days, “we had some great times. It was us against the Japs, we could have been beaten or killed at any time, and some were! It sounds crazy, but the danger was exciting.” There were many camp reunions over the years in the US, and the UK as well, and Ed went to most of them.

I recall Ed coming to our house in Shanghai to collect a suitcase he had left with us in 1940. Briefly out of camp, he was handsome and optimistic. Di, my mother commented “Ed’s sign is the horse; that definitely describes him.” The horse in Chinese lore is meant to have a cheerful disposition and flattering ways that makes it a popular favorite, also being someone with great mental agility. “that’s Ed,” Di added, “he could have been a con man or a smuggler or worse if I hadn’t kept him on a short lease when he was a boy.”

Of course, she didn’t see herself as having aided a smuggler as his secretary. When her employer left Shanghai, he handed her a suitcase of US dollars as her reward. At a dinner party later, Di reminisced “I couldn’t wear my good high heels on that job. Frequently I had to dash down the back stairs ahead of the police! His bodyguard would be right ahead of me, carrying my typewriter! And the files that could land us all in jail.” So many stories floated around back then, most very colorful, hardly believable, but usually true. Grubby sampans floated down the Yangtse river, loaded with drugs, arms and other contraband. Even my natty Dad would receive a coded telegram followed by a visit to his office by a ragged delivery boy with an interesting load. Ed was either too young or in concentration camp to be connected to this lucrative smuggling network. All he wanted, once out of camp, was to get out of this doomed society, and he did. My Dad, Hans, may have made a pile importing weapons, but this ammunition was ultimately used by the Communists to take over the city. Everything my family owned was stripped away. “Lost!” my mother would moan, “All lost. Everything gone. Nothing to show for all we worked so hard for.” Two houses, with their customized contents; a farmed plot in the countryside; a Rover car, a paper box factory, and more: all confiscated by the new regime. She soldiered on, working hard in England and the U.S., but she never got over her losses.

By the time I met Ed again in the ’50s in California, where I had gone for college, he was a sober family man, with a young son and a well paying job with Brown Forman Distillers. His wife, Ellen, was a stay at home mom, and they went on to raise three more children in their sprawling, ranch style house. All four children grew up tall, healthy, with all their teeth. Wartime camp survivors would have major dental problems the rest of their lives. Many had stunted bodies and lifelong internal parasites. They could never forget years of being half starved and constantly fearful of their captors. Many desperately needed to relive some of those times in the reunions that they went to year after year.

Ed didn’t care to share his stories with his children. His family was his new life; his hard won success story. His children all got a college education, good jobs, mainly happy marriages and a similar secure future for their children. Ed and Ellen had a long life together and died within a few years of each other.

photos: Ed in September 1945

Ed’s sleeping space

Shoveling coal for cooking

Ed and Dan Holden

Ed and Ellen’s wedding

Deaths, listed in the Shanghai Gazette:

On May 11, 1942, at her residence, 606 Embankment Building, Shanghai, Mrs. Mary Klyhn, aged 72 years, widow of the late Lauritz H.C. Klyhn and mother of Mrs. Burgoyne, Mrs. Davie, Mrs. Fulton, Peter, Lawrence, Hans and Harry Klyhn. Funeral services will be held at the Bubbling Well cemetery on May 13.

The grave of Mary, or Ah Fang, as she was listed on her marriage certificate, was surrounded by dozens of floral tributes. The list of donors included Chinese, and Eurasians of several mixes: Portuguese, Indian, Danish, and German. I was on the list, with my parents, and I can recall the grave, smothered in bouquets. A red maple tree was planted by the grave. By the time most of the family left for other countries in 1949, the tree was a spectacular signpost to the grave. Today, the cemetery is long gone, and high rise buildings have taken its place.

But my question is: who was she? I know she was tiny…and her husband at least a foot taller. They had met in Ockseu, Amoy, where he held the post of the lighthouse keeper. As far as I know, she barely spoke English, and Lauritz certainly did not communicate in her Hakka dialect. How did a Danish six footer get together with a Chinese woman under five foot tall?

They were legally married, and as we know,  had seven children in Ockseu.

had seven children in Ockseu.

Lauritz died suddenly in his forties, and Ah Fang was counseled by locals to get herself and her children to Shanghai, where missionaries were reputed to be helpful. None of the children, then all under ten years old, ever were told how this transpired. Part of the mystery of Ah Fang is how a penniless, illiterate woman achieved this transfer, and soon saw all her children housed, fed, clothed and schooled. The Presbyterian missionaries who embraced the family saw to it that the children were enrolled in charity schools, where they received an excellent education and emerged ultimately as skilled accountants and secretaries. Eurasians may have been pariahs socially, but they were eminently employable. They were smart, skilled, willing to work harder and agree to far less pay than their white colleagues.

My recollection of Ah Fang is of a figure in a darkened room in the Embankment Building apartment of my aunt Grace and her husband, Bob. I remember visiting, and being told “you can go in to see Granny now.” Reluctantly, I entered the room, where Ah Fang, now dubbed Mary, lay in a canopied bed by the curtained window. She was slowly succumbing to a painful cancer. I remember the sweetish fug that filled the room…Mary was almost immobile and never spoke to me. Her hands might rise from the bed and she might tremulously ball up a paste and stuff it in a pipe. Her amah would light it for her, and she would smoke for a few moments, then seem to fade into her bed. Sometimes she would cough; quite a strong, hacking sound, and the bed would vibrate. That was it. I was never tempted to approach the bed, and I was glad to leave the room, feeling a bit dizzy. Aunt Grace always had a slice of cake for me. Her son, Ron, a few years older than me, would be out or on his way to a soccer game with his father Bob, a tall, handsome and well regarded player. Bob Davie, too was on his way, soon to join the British army on the fight against Japan. Grace was a small and saintly figure at our often raucous family parties. Taking care of her mother was her primary duty. Her son claims my opium smoking recollection was a fantasy, but he does admit that Grace supplied her mother with heroin by injection, as needed. But none of this tells me anything about the woman herself. In a photo of her 60th birthday, she sits, as always in her Chinese padded gown, in the midst of an extended family in a typical Chinese restaurant of the day.

The food would be excellent and plentiful, but the furnishings were typically austere; complete with hard backed chairs, wobbly tables and clammy tile walls and floor. The same cast of characters, plus a few more, would be present at her funeral.

The food would be excellent and plentiful, but the furnishings were typically austere; complete with hard backed chairs, wobbly tables and clammy tile walls and floor. The same cast of characters, plus a few more, would be present at her funeral.

photos:

Lauritz with one of his children,

Ah Fang (Mary)

the lighthouse,

the 6oth birthday party

I started the blog to shar e my history with my son, Jack Pestaner, and I dedicate this work to him, with lots of love. Jack with his dog, Buffy.

e my history with my son, Jack Pestaner, and I dedicate this work to him, with lots of love. Jack with his dog, Buffy.

Jack also dragged me into the 21st century with his patient coaching in the technical details of blogging.

As soon as I began writing, inspired by the Phyllis Shute photo albums and her extensive notes sent to me by her younger son, Trevor (whose name I changed in the blog for privacy reasons) I needed to do additional research. I started to google, and acquired a few very important correspondents.

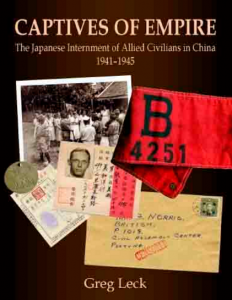

Greg Leck is the author of Captives of Empire: the Japanese Internment of Allied Civilians in China, published in 2006. This is an exhaustive history of the period, and a beautiful book full of photos, documents and even the names of the internees, including my relatives. Greg provided me with a photo of the Imperial Seal, a copy of which he has framed in his home today. Greg has always been ready to dig into his archives to answer my many questions on this period.

Graham Earnshaw is a publisher of quality books on China; more information at earnshaw.com. Graham encouraged me to continue my blog and provided me with some good photos.

Graham Earnshaw is a publisher of quality books on China; more information at earnshaw.com. Graham encouraged me to continue my blog and provided me with some good photos.

Patrick Cranley is an American expert in the architecture, history and urban development of Shanghai. He was an organizer of the 2015 Shanghai Art Deco World Congress, as well as a creator of Historic Shanghai, an excellent site with tours, lectures and book promotions about Shanghai. Patrick lives in Shanghai, and when I first contacted him for help with my blog, it turned out that he lives in a building right behind one of my homes on the former Rue Boissezon! Patrick has sent me photos of my old homes, both on that road, but sadly diminished.

Who would have guessed that in my search for Shanghai Millionaire material, I’d run into Kent McKeever (via Google), the director of the law library at Columbia University! Kent generously opened up his collection for me to have a good look and a go down memory lane. Kent’s office was full of books and papers about old Shanghai, including a 1940 phone book, with listings of my various family members.

I realize now that there many people all over the world to whom Shanghai in the 30’s and 40’s is still very much alive. Their interest is helping preserve some of the beautiful architecture of that period. A brilliant book on that subject is A Last Look: Western Architecture in Old Shanghai, by Tess Johnston, photos by Deke Erh.

So to all who subscribed to joanshanghai.co thank you for your staying power through so many posts. If you loved that period, check out some of the references I listed above. Be sure to contact Patrick Cranley if you decide to visit Shanghai, as he will have many adventures to propose and even take you on.

Lastly, I take responsibility for everything I have written, but with the caveat that I write from personal memory. Some readers may disagree with my take on them. To them, I apologize. The past is vivid for me, but I can’t vouch for every detail. If, as I did, you lived through that time please recall that it was a long time ago, and not all stories played out the same for the different players!

Granny is the one I remember with the most love . She was Chinese, born in the 1860’s. Her father was supposedly an intellectual who refused to have her feet bound. This practice was not officially abolished till 1911 or 1912, and we had a favorite Amah with bound feet in our household through the 40’s.

. She was Chinese, born in the 1860’s. Her father was supposedly an intellectual who refused to have her feet bound. This practice was not officially abolished till 1911 or 1912, and we had a favorite Amah with bound feet in our household through the 40’s.

So Granny grew to adulthood with no marriage prospects. She trained as a midwife, and worked as one all her life, called on day or night to deliver babies. People didn’t have much money, so they often paid her in eggs, a chicken, or a slab of meat. Grandpa, who we suspect was English, as his name was Maitland, was a shadowy figure. He was very old and practically blind when I knew him. He had been a telegrapher, sending out messages in Morse code for the Northern Telegraph Company. We don’t know how he met Granny, but they got married and had eight children, from 1885 all the way to 1910. The Maitland children were all very good looking, and definitely upwardly mobile Eurasians. Someone else will tell their fascinating history; we’ll just stick to Granny and Mary, our mother, the oldest Maitland child, who died in childbirth in her late 30’s.

After mother’s sudden death, our father decamped on a boat to Harbin without notice. Granny stepped in, and became our informal mother figure, a job officially taken on by my sixteen year old sister, Daisy. While Daisy worked as a secretary, Granny tried to spoil us, cooking fantastic meals which I remember eating to this day. By then, grandpa had passed…that wizened figure curled up in one of our unforgiving wooden chairs, poring over a book, his nose an inch away from the text. One day, he was gone. Granny, though, was full of energy. She was tall, with big feet. We would later tease our niece, Joan, that her great grandma had bequeathed those feet to her!

So, this was the end of the Szechuan road house that grandpa had purchased many years ago for his growing family. We gave up all our perks, squeezed ourselves into smaller quarters. Thanks to Daisy’s  efforts, we all got into good schools when we were old enough, and miraculously, got into the Embankment building after her marriage to Hans Klyhn.

efforts, we all got into good schools when we were old enough, and miraculously, got into the Embankment building after her marriage to Hans Klyhn.

Our life was never a step by step progress. We seemed to lurch from crisis to crisis, but our city was awash in opportunities. So while we had a serious setback after mother died, it did not take very long for us to make our way back. I believe it was Daisy, who was able to seize every chance to move forward. It’s hard to imagine today the power and connections a secretary had back then. Daisy was the anchor for some really crazy entrepreneurs, who were gunrunning along the Yangtse River, supplying revolutionary activity of every sort, or moving tons of drugs, and probably human cargo. Impeccably dressed from head to toe, with her steno notebook in hand and typewriter by her side, Daisy was the indispensible normal face of her employer. At home, she suffered from migraine headaches and agonizing menstrual cramps, but nothing stopped her from pushing her brothers and sisters forward.

I am always grateful I had the privilege of taking care of her when she was dying. Finally, she lay there in the hospice, in a Canadian town, a cigarette clutched in her gnarled hand to the very last. What a struggle her life had been from the beginning to the end!

Granny

The Thomas Hanbury School we girls attended. There was also a Thomas Hanbury school attended by the boys.

Our family home from the late 19th century was at 234 North Szechuan Road. It was the first house in the alley. You entered the front door on the wall of the row of houses, and stepped into a flag stone courtyard. Our water supply was a cold water tap on the right hand corner; all our household water was drawn from this tap. The ground floor was the kitchen and the servants’ quarters. Up a flight was the middle floor, mainly consisting of a large living room. Hard backed wood chairs were ranged against the wall on either side of the room, with an end table by each chair. At the back was a large wood chesterfield, with a porcelain pillow for reclining. Not a cushion in sight! No place to lounge or to slouch!

Up a flight was the middle floor, mainly consisting of a large living room. Hard backed wood chairs were ranged against the wall on either side of the room, with an end table by each chair. At the back was a large wood chesterfield, with a porcelain pillow for reclining. Not a cushion in sight! No place to lounge or to slouch!

Next to it was a dining room with a large round table and more hard backed chairs. At least there was a pot bellied stove in one corner, but it didn’t do much, as drafts blew through the whole house through gaping windows and doorways. You bundled up in winter, and sweated through the muggy summer. Central heating, air conditioning, double glazing, even doors that closed were unheard of.

The top floor and attic contained our many bedrooms, and above, there was a flat topped roof garden, or sai pang, where the servants hung our laundry out to dry. There would often be a relative staying in one of the bedrooms, often we didn’t realize they were around until they joined us at mealtimes.

My mother had a houseful of servants; each one of us had a young companion, an Ah Mei. The source of these servants was a seemingly constant supply of unwanted girl babies. They were given away, sold, or discarded and left to die in the street. Mother took in many of these children, fed and nurtured them and kept them in the house as Ah Mei’s and eventually as full fledged help, or Amahs. They were taught household skills by the older servants, and mother eventually got husbands for some of them. Later they would come and visit her, bringing their children to show her. Mother got a great deal of satisfaction from this, as well as a fund of home help. My girlhood friend Nell recalled “your living room was always a scene of chaos. Kids would be running around, servants of every age were doing some job or other or chasing the children, and your mother in the middle, looking calm and happy, drinking tea. I always felt that anything could happen!”

My parents had a shop directly across from our home, selling yard goods, perfumes and toiletries, mostly imported from Russia. Other items were obtained “on the side” by my mother, who would go to the wharf with a couple of bodyguards when a large ship came in. She would pack the pockets of her special shabby padded Chinese gown with different denominations of cash, and would troll the docks for sailors who had valuables to sell. There were stories of shipwrecks, kidnappings and general thievery, but no specifics. Mother would come back and produce interesting goods, even expensive jewelry, at times, and there would always be well dressed customers coming around the shop at odd hours to check out this merchandise. I vaguely recall a story of a vanished diamond that eventually turned up in a trouser cuff, apparently dropped by accident. Mother guarded the door and no one could leave till the diamond was recovered. True? Or did I imagine it?

Apart from the bodyguards, who were always needed, as all transactions were in cash, there were several salesmen; it was a very prosperous business. The shop was open in design; you just walked in off the street. The merchandise was displayed in several plate glass cabinets.

There were no automobiles in our day. There was a good tram service and plentiful rickshaws. My parents owned a carriage and a horse, with a mafoo, or driver on hand to take us wherever we wanted to go. All six children would pile in for a ride to the country with a picnic. These events were never planned; they just seemed to happen in that crowded life we led.

Typical chair/table arrangements at the time

Phyllis; at the photography studio

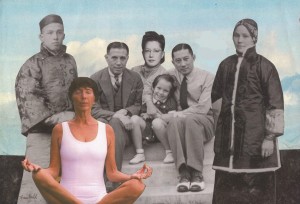

This collage, made for me by my artist friend, Joan Hall, pulls together a big part of my lineage.

On the right and left, are my Eurasian grandparents, James and Mary, in Chinese dress. Grandfather, again, this time in Western clothes re-appears after a disappearance of many years after Mary’s death. He looks subdued, as he should have, after abandoning his family for years, and then re-appearing, broke. But because of his innate good nature and willingness to do whatever odd job came up, he managed to re-insert himself into the family, living with various sons and daughters, and making himself useful, with few demands. He was a tall, handsome man, with good posture and good social skills. He wasn’t bright, but made up for it with his good looks, amenable nature and his smooth foxtrot on the dance floor. I loved grandpa, as did every kid he met. He was always ready to play games with us, and tell goofy jokes.

He wasn’t bright, but made up for it with his good looks, amenable nature and his smooth foxtrot on the dance floor. I loved grandpa, as did every kid he met. He was always ready to play games with us, and tell goofy jokes.

There’s my mother, her hair in a stylish updo , looking out with her no nonsense gaze. Then, there’s my father, characteristically with his arms around me.

He would say to me, so often “Don’t worry. Dad won’t let anything bad happen to you,” or variants on that theme. He meant it, and on our last day in Hongkong, as he stood on a swaying pontoon, feeling seasick, watching me embark  on a ship to California, he stuffed an envelope into my hand. $500 US dollars back in 1953 represented a big part of his meager savings. My mother, whose strong stomach would carry her through many more travels through her life, stood by grimly. As always, she was disappointed in me. I had failed typing, shorthand, sewing and knitting training, all of which might have helped me get a job to help the family out. At seventeen, I had no interest in spending any more time with my warring parents. Earning my living with a proper job was way in my future. I was off to the College of Notre Dame in San Mateo, California, on a partial scholarship. I had to perform some menial work, in return, with my laughable skills. The story of my induction into the real world is not part of this narrative, except that I need to acknowledge, after all these years, the kindly souls who imagined I could do well at a lunch counter, or later as an au pair. The latter work was in exchange for a lovely attic room, when I escaped ungratefully from the suburban College to the wide open world of the University of California at Berkeley. My housekeeping was abysmal, but my hosts were a charming, academic couple, who took a while to wake up to their messy home. This could have been because they spent their evenings at home drinking one martini after the next before slowly making their way to bed. They eventually hired a maid and gently phased me out after a year.

on a ship to California, he stuffed an envelope into my hand. $500 US dollars back in 1953 represented a big part of his meager savings. My mother, whose strong stomach would carry her through many more travels through her life, stood by grimly. As always, she was disappointed in me. I had failed typing, shorthand, sewing and knitting training, all of which might have helped me get a job to help the family out. At seventeen, I had no interest in spending any more time with my warring parents. Earning my living with a proper job was way in my future. I was off to the College of Notre Dame in San Mateo, California, on a partial scholarship. I had to perform some menial work, in return, with my laughable skills. The story of my induction into the real world is not part of this narrative, except that I need to acknowledge, after all these years, the kindly souls who imagined I could do well at a lunch counter, or later as an au pair. The latter work was in exchange for a lovely attic room, when I escaped ungratefully from the suburban College to the wide open world of the University of California at Berkeley. My housekeeping was abysmal, but my hosts were a charming, academic couple, who took a while to wake up to their messy home. This could have been because they spent their evenings at home drinking one martini after the next before slowly making their way to bed. They eventually hired a maid and gently phased me out after a year.

I return to the collage. Yes, there I am, hugged by my Dad, feeling so very protected. Dad, as always, is impeccably dressed. I would squat in the kitchen and watch Xiao Liu polishing Dad’s two tone shoes to perfection. When he was done, I’d snatch them and dash upstairs to Dad’s bedroom. I’d slide open the well oiled doors to Dad’s wall to wall closet. There were shelves for everything. Dozens of pairs of shoes, each ensconced in its shoe tree, suits for every occasion, tie racks, handkerchief slots, socks divided by color, and shirts and more shirts, underwear, and a very special rack on the top for his hats. I always looked for the Borsalino hat I had saved up for with the money Dad used to slip me. When I had accumulated enough, I enlisted Uncle Sam to get Dad’s measurements and to take me to the shop. There I gave my wadded up stash to the amused salesman, and left with a magnificent hat box containing (I believed) a magnificent hat. Dad certainly wore it, and always told whoever was present that it had been my gift. There it was, on the shelf, fitted over its hat shape. There were accessory drawers, too, for cufflinks, tie clips, watches, and elastics Dad would wear around his upper arms to prevent his shirt cuffs from protruding too far out of his jacket sleeves. I’d slide open the closet doors and gaze in awe at this presentation of hanging suits, coats and shirts, and shelves and drawers of every size. Dad was a dandy, and his glossy black, slicked back hair with its side part seemed to stay with him most of his life. My mother, though, was sloppy. My own nature has often been a clash between sloppiness and tidiness. The latter has won out now that I live in a tiny New York studio apartment. When my mother got ready for a party, she would carefully apply her make up and fix her hair, often with a hairdresser on hand; wrap a cheesecloth over her face and hair, and then slip on her dress. The wrap prevented any makeup smear or hairdo disruption. Again, dressing up was a process, taking time. Occasionally I was allowed to watch, and perhaps pass a hairpin or so. But while she looked elegant as she left her room, her dressing table was a mess of makeup, perfumes and various brushes and sponges. Rejected dresses and shoes were scattered all over the room. Amah and a helper would go in after mother left and spend the evening tidying up.

There were accessory drawers, too, for cufflinks, tie clips, watches, and elastics Dad would wear around his upper arms to prevent his shirt cuffs from protruding too far out of his jacket sleeves. I’d slide open the closet doors and gaze in awe at this presentation of hanging suits, coats and shirts, and shelves and drawers of every size. Dad was a dandy, and his glossy black, slicked back hair with its side part seemed to stay with him most of his life. My mother, though, was sloppy. My own nature has often been a clash between sloppiness and tidiness. The latter has won out now that I live in a tiny New York studio apartment. When my mother got ready for a party, she would carefully apply her make up and fix her hair, often with a hairdresser on hand; wrap a cheesecloth over her face and hair, and then slip on her dress. The wrap prevented any makeup smear or hairdo disruption. Again, dressing up was a process, taking time. Occasionally I was allowed to watch, and perhaps pass a hairpin or so. But while she looked elegant as she left her room, her dressing table was a mess of makeup, perfumes and various brushes and sponges. Rejected dresses and shoes were scattered all over the room. Amah and a helper would go in after mother left and spend the evening tidying up.

Finally, there is the Joan of today, in a yoga posture, a yoga instructor in New York City. Behind me, the ghosts of my past. The grandparents on either end need their story told, so I’ll hand that over to their daughter, Phyllis.

collage by Joan Hall

grandpa back home

the Castleville, decommissioned, years after I sailed on it

Dad in Hongkong