Ed’s 5’10” body was down to 118 pounds when his camp at Pootung was liberated in August 1945. For the past three years, he had slept on a wooden plank, his belongings hung overhead.

Ed’s 5’10” body was down to 118 pounds when his camp at Pootung was liberated in August 1945. For the past three years, he had slept on a wooden plank, his belongings hung overhead.

He shoveled coal for the cooking fire, as part of the kitchen detail, scrounged for food every day, and in the process, formed great friendships with the Americans he worked with.

Ed recalled his time in camp as a great adventure. “Our kitchen team woke up every day trying to figure out how to score some food. Rodents, roaches, a dog from the Canidrome, which had been slaughtered by the Japanese, wormy rice, animal feed: these were some of our finds. We got together to collect any valuables we could trade over the fence with the Chinese vendors. By the end there wasn’t a watch, belt buckle or piece of jewelry left to any of us. I had to reluctantly let go of my dancing shoes. Why had I even thought of packing them for camp in the first place? ” Ed could not have realized at the time that his excellent ballroom dancing might later help get him into the USA. But that comes later.

Ed recalled his time in camp as a great adventure. “Our kitchen team woke up every day trying to figure out how to score some food. Rodents, roaches, a dog from the Canidrome, which had been slaughtered by the Japanese, wormy rice, animal feed: these were some of our finds. We got together to collect any valuables we could trade over the fence with the Chinese vendors. By the end there wasn’t a watch, belt buckle or piece of jewelry left to any of us. I had to reluctantly let go of my dancing shoes. Why had I even thought of packing them for camp in the first place? ” Ed could not have realized at the time that his excellent ballroom dancing might later help get him into the USA. But that comes later.

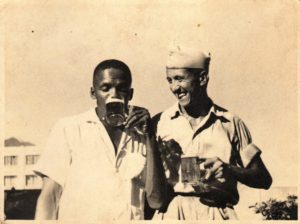

On August 19, 1945, A huge Curtis C-46 Army Transport arrived at Dazang Airfield in Shanghai on an American goodwill mission. The aim was to arrange the orderly release of Allied internees. The behemoth plane first brushed over the dingy Pootung internment camp building, with its 1700 horsepower cyclone motors roaring and an American officer waving madly from it. As soon as the inmates identified the US insignia on the plane, they went wild. They erupted from their quarters like a tidal wave. Everyone was doing something: waving flags, shouting or stomping with joy. The Japanese had disappeared. Leaflets floated down with various instructions to the inmates, “But all we needed to know is: it’s over!” Ed recalled. Soon the party began. Food, cigarettes and beer appeared over the fence. Ed celebrating here with his best friend, Dan Holden. “

We’ll meet again in California” Dan vowed. And they did, even though it didn’t work out the way they expected.

We’ll meet again in California” Dan vowed. And they did, even though it didn’t work out the way they expected.

The internees made their way home, mainly to the US. Ed found a job in Hongkong, gathered his meager belongings and moved there in 1948. This was just a waystation for him; he was determined to go to the US.

Soon after, at a dance at the Peninsula Hotel, he met Ellen, an American nurse. She recalls “he was the best dancer I had ever met. ” Ed said the same about her. They danced a whole week away every night. On his time off, he took her for picnics at the beach at Repulse Bay, where he was very impressed by her body. Ellen was a strict Catholic, so they never got beyond her boundaries. She had to return home shortly to the US, and that could have been the end of it. But she returned to Hongkong in 1949. “I couldn’t stop thinking about Ed, and how we danced and danced. People at the Peninsula used to back away and watch us. I felt like a star!”

They reunited and that same year they got married at St. Teresa’s Catholic church in Hongkong.  Ellen immediately started the procedure of getting Ed to the US. He qualified as a War Bride, and they were soon on their way to California. Years later, when one of their children asked Ellen about it, she said “it was his dancing that did it for me!” And they stayed together, raising four children. His friendship with Dan Holden did not survive the racial prejudice of the ’50s, something both always regretted.

Ellen immediately started the procedure of getting Ed to the US. He qualified as a War Bride, and they were soon on their way to California. Years later, when one of their children asked Ellen about it, she said “it was his dancing that did it for me!” And they stayed together, raising four children. His friendship with Dan Holden did not survive the racial prejudice of the ’50s, something both always regretted.

For a young, unattached man, the rigors of a concentration camp were balanced out by the strong male bonding that brought the disparate men together. “We were at our best,” Ed told me later, though he rarely spoke of those days, “we had some great times. It was us against the Japs, we could have been beaten or killed at any time, and some were! It sounds crazy, but the danger was exciting.” There were many camp reunions over the years in the US, and the UK as well, and Ed went to most of them.

I recall Ed coming to our house in Shanghai to collect a suitcase he had left with us in 1940. Briefly out of camp, he was handsome and optimistic. Di, my mother commented “Ed’s sign is the horse; that definitely describes him.” The horse in Chinese lore is meant to have a cheerful disposition and flattering ways that makes it a popular favorite, also being someone with great mental agility. “that’s Ed,” Di added, “he could have been a con man or a smuggler or worse if I hadn’t kept him on a short lease when he was a boy.”

Of course, she didn’t see herself as having aided a smuggler as his secretary. When her employer left Shanghai, he handed her a suitcase of US dollars as her reward. At a dinner party later, Di reminisced “I couldn’t wear my good high heels on that job. Frequently I had to dash down the back stairs ahead of the police! His bodyguard would be right ahead of me, carrying my typewriter! And the files that could land us all in jail.” So many stories floated around back then, most very colorful, hardly believable, but usually true. Grubby sampans floated down the Yangtse river, loaded with drugs, arms and other contraband. Even my natty Dad would receive a coded telegram followed by a visit to his office by a ragged delivery boy with an interesting load. Ed was either too young or in concentration camp to be connected to this lucrative smuggling network. All he wanted, once out of camp, was to get out of this doomed society, and he did. My Dad, Hans, may have made a pile importing weapons, but this ammunition was ultimately used by the Communists to take over the city. Everything my family owned was stripped away. “Lost!” my mother would moan, “All lost. Everything gone. Nothing to show for all we worked so hard for.” Two houses, with their customized contents; a farmed plot in the countryside; a Rover car, a paper box factory, and more: all confiscated by the new regime. She soldiered on, working hard in England and the U.S., but she never got over her losses.

By the time I met Ed again in the ’50s in California, where I had gone for college, he was a sober family man, with a young son and a well paying job with Brown Forman Distillers. His wife, Ellen, was a stay at home mom, and they went on to raise three more children in their sprawling, ranch style house. All four children grew up tall, healthy, with all their teeth. Wartime camp survivors would have major dental problems the rest of their lives. Many had stunted bodies and lifelong internal parasites. They could never forget years of being half starved and constantly fearful of their captors. Many desperately needed to relive some of those times in the reunions that they went to year after year.

Ed didn’t care to share his stories with his children. His family was his new life; his hard won success story. His children all got a college education, good jobs, mainly happy marriages and a similar secure future for their children. Ed and Ellen had a long life together and died within a few years of each other.

photos: Ed in September 1945

Ed’s sleeping space

Shoveling coal for cooking

Ed and Dan Holden

Ed and Ellen’s wedding