Granny is the one I remember with the most love . She was Chinese, born in the 1860’s. Her father was supposedly an intellectual who refused to have her feet bound. This practice was not officially abolished till 1911 or 1912, and we had a favorite Amah with bound feet in our household through the 40’s.

. She was Chinese, born in the 1860’s. Her father was supposedly an intellectual who refused to have her feet bound. This practice was not officially abolished till 1911 or 1912, and we had a favorite Amah with bound feet in our household through the 40’s.

So Granny grew to adulthood with no marriage prospects. She trained as a midwife, and worked as one all her life, called on day or night to deliver babies. People didn’t have much money, so they often paid her in eggs, a chicken, or a slab of meat. Grandpa, who we suspect was English, as his name was Maitland, was a shadowy figure. He was very old and practically blind when I knew him. He had been a telegrapher, sending out messages in Morse code for the Northern Telegraph Company. We don’t know how he met Granny, but they got married and had eight children, from 1885 all the way to 1910. The Maitland children were all very good looking, and definitely upwardly mobile Eurasians. Someone else will tell their fascinating history; we’ll just stick to Granny and Mary, our mother, the oldest Maitland child, who died in childbirth in her late 30’s.

After mother’s sudden death, our father decamped on a boat to Harbin without notice. Granny stepped in, and became our informal mother figure, a job officially taken on by my sixteen year old sister, Daisy. While Daisy worked as a secretary, Granny tried to spoil us, cooking fantastic meals which I remember eating to this day. By then, grandpa had passed…that wizened figure curled up in one of our unforgiving wooden chairs, poring over a book, his nose an inch away from the text. One day, he was gone. Granny, though, was full of energy. She was tall, with big feet. We would later tease our niece, Joan, that her great grandma had bequeathed those feet to her!

So, this was the end of the Szechuan road house that grandpa had purchased many years ago for his growing family. We gave up all our perks, squeezed ourselves into smaller quarters. Thanks to Daisy’s  efforts, we all got into good schools when we were old enough, and miraculously, got into the Embankment building after her marriage to Hans Klyhn.

efforts, we all got into good schools when we were old enough, and miraculously, got into the Embankment building after her marriage to Hans Klyhn.

Our life was never a step by step progress. We seemed to lurch from crisis to crisis, but our city was awash in opportunities. So while we had a serious setback after mother died, it did not take very long for us to make our way back. I believe it was Daisy, who was able to seize every chance to move forward. It’s hard to imagine today the power and connections a secretary had back then. Daisy was the anchor for some really crazy entrepreneurs, who were gunrunning along the Yangtse River, supplying revolutionary activity of every sort, or moving tons of drugs, and probably human cargo. Impeccably dressed from head to toe, with her steno notebook in hand and typewriter by her side, Daisy was the indispensible normal face of her employer. At home, she suffered from migraine headaches and agonizing menstrual cramps, but nothing stopped her from pushing her brothers and sisters forward.

I am always grateful I had the privilege of taking care of her when she was dying. Finally, she lay there in the hospice, in a Canadian town, a cigarette clutched in her gnarled hand to the very last. What a struggle her life had been from the beginning to the end!

Granny

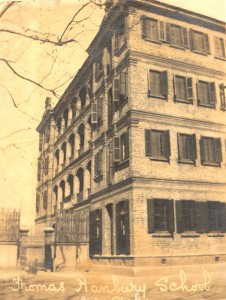

The Thomas Hanbury School we girls attended. There was also a Thomas Hanbury school attended by the boys.