My aunt Phyllis has been a model tenant at Stone Lodge assisted living center in Guelph in Canada for about fifteen years. Unfortunately, the police had to be called in last week after an altercation involving her and her roommate, Mrs. Wilkins.

My cousin Kevin was sitting in his nearby backyard trying to enjoy a cold beer, when he, too, got a call from the Lodge. A bad dust-up was reported. Big drama! “Normally, the only drama at the Lodge is at mealtimes,” Kevin told me. “Sixty oldsters race their walkers along several hallways, and converge at the single entrance to the dining room. It’s like the chariot race in Ben Hur! That’s as exciting as it usually gets.”

This time, Mrs. W intercepted Phyllis in the lounge, and according to staff witnesses, accused her roommate of stealing her clothes and jewelry. Phyllis then turned her walker around and tried to move away, when Mrs. W. picked up a magazine and hit her on the back, shouting “thief!”

This was too much for Phyllis, who turned, made a fist and punched Mrs. W. in the face, knocking her over.

In the resulting melee, the police arrived to take down details. It seems Mrs. W. had a history of accusing both staff and roommates of thieving. She was on her third roommate. She didn’t take her Meds regularly. And a bruise was beginning to show on her face. Her dentures were askew. Phyllis, who had thrown the punch, was not on any Meds, had the reputation of being a quiet and pleasant reader and was a member of the Scrabble club. All witnesses were on her side.

Kevin arrived at the Lodge, just as the police were interviewing the ladies. Mrs. W was very agitated, but reluctantly admitted to being 88 years old. When they got to Phyllis, the police found her sitting quietly, with her hands folded in her lap. “I never took her things,” was all she said, in her calm way.

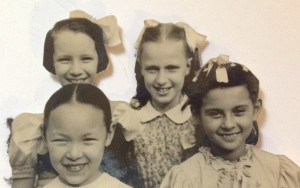

They could not know this woman had lived through wars, incarceration in a  concentration camp, revolution, and a hasty escape from Communist China with two small children in tow. That a journey back then on an old ship from England to Canada, barely paid for, could not be missed or all would be lost.

concentration camp, revolution, and a hasty escape from Communist China with two small children in tow. That a journey back then on an old ship from England to Canada, barely paid for, could not be missed or all would be lost.

“ I had mumps when mom had to get me on the ship” Kevin reminded me later, “I was screaming nonstop, so I had to be bundled up, almost suffocating, as they wouldn’t have let me on board if they’d known I had mumps.” With steely determination and perfect aplomb, Phyllis got the little family to their destination, the very town she where she now resided in her final years.

“And your age, madam?” was their last question. “A hundred and one, ” Phyllis replied. Did she have a little smile on her face when the three police officers started to roar with laughter? Kevin reported to me that they totally cracked up. He had to laugh himself, especially when one of them held out his hand to Phyllis and chortled “madam, I’d like to shake that hand of yours!”

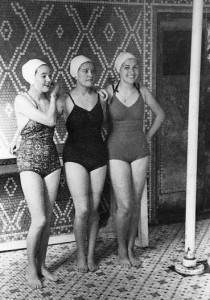

photo of Phyl and husband Jack in Shanghai in 1938

ther received a stream of service providers all day long. They included the psychiatrist, the masseur, the cosmetologist, the dressmaker, the hairdresser, the manicurist, and more. She also had a regular mahjong group as well as a bridge group. My father, my mother and I each had our own suite of rooms, and we were taken care of by a crew of se

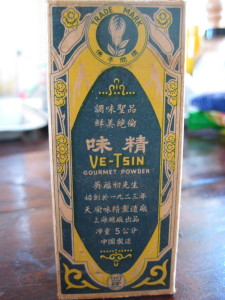

ther received a stream of service providers all day long. They included the psychiatrist, the masseur, the cosmetologist, the dressmaker, the hairdresser, the manicurist, and more. She also had a regular mahjong group as well as a bridge group. My father, my mother and I each had our own suite of rooms, and we were taken care of by a crew of se rvants who inhabited our large house more fully than we did. For me, the vibrant center of the house was the kitchen. I’m told that, starting as a baby, I would crawl around the tiled floor, picking up bits of detritus and usually eating them. I grew up in that kitchen. Later, I’d head there as soon as I got home from school.

rvants who inhabited our large house more fully than we did. For me, the vibrant center of the house was the kitchen. I’m told that, starting as a baby, I would crawl around the tiled floor, picking up bits of detritus and usually eating them. I grew up in that kitchen. Later, I’d head there as soon as I got home from school.